In Conversational Solfege (CS) the recommended amount of time spent in the Writing Steps (9-12) is significantly less than that spent developing conversational skills at Steps 2-5 (Conversational Solfege.) After mastering the Reading Steps in a unit, it’s natural for students to want to move on to create through writing, and since CS places the conversational thinking of music before the composing step, children learn to imagine what they want first before trying to render it on paper. Child Psychologist Jane Healy describes this same concept for language development.

“Well-reasoned and well-organized writing proceeds from a mind trained to use words analytically. No matter how good, how creative, or how worthy a student’s ideas, their effectiveness is constrained by the language in which they are wrapped. (Writing) demands a firm base of oral language skill. Students who have not learned to line up words effectively when they speak are not going to be able to do so on paper.” Endangered Minds, Jane Healy 1990, page 110.

Through the lens of preference development in children, that is a very empowering concept. I cannot present a study to support this claim, but maybe you agree with this next statement: when people imagine what they desire before attempting to render the idea, they tend to be more inventive, more free from constraints of what lies only before the eyes and more able to tap into what lies below the surface and communicate the expressive musical thoughts that originate in their inner hearing.

I’ve always had a portion of my students whose writing was never as good as their efforts at the Conversational Solfege and Reading Steps. As I looked around the school at their other work, the same was often true in other subjects. After speaking with some writing and occupational therapists, I made accommodations with a writing desk, the angle of paper, the color of paper and the type of pencil/pen. Each adjustment gave varying results but it was difficult to say if any actually led to improvement in notational legibility. Providing beat space lines yielded the clearest results.

I’m one of these people too. My handwriting is illegible to most people reading it, so my heart goes out to these kids. Because of this I think of how I can encourage them to slow down and take their time writing and imagine the intended shape in a way that doesn’t embarrass them.

A teaching mentor of mine, who happened to have meticulous penmanship herself, would get great results in her own class writing assignments. I credited her taking time to teach the calligraphy of notation, sparking artistic interest in students, while reviewing the steps to form each figure, directing hands to “place the tip of pencil a finger width above the note-head” and “connect to the note-head with a perfectly straight line.” She took time to review the steps and vocabulary repeatedly while the kids practiced writing notes, much like they do with alphabet letters in Kindergarten and 1st grade. Her directions gave the spatially challenged students time to think and review the steps to making neat notation while allowing others a chance to show how talented they are in making musical notation.

Some possible phrases to speak to encourage good notation penmanship

- “Strive for neat noteheads.“

- “Use consistent size of oval shaped note heads.”

- “Check that stems are placed on the correct side of the note head.”

d’s and p’s not b’s & q’s

- “Make stems straight and attached to the notehead “

- “Draw stems the height of the staff.”

Fast forward a few years and I found myself teaching in a community with extraordinarily low literacy rates resulting from systemic poverty. Beyond the above-mentioned encouraging phrases, these children needed deep involvement in the writing process to help set the seeds for the fact that literacy is power, and writing/creating is the pinnacle of that power. I found the help I sought as I discovered activities that could exercise the writing process in the “Techniques” section of the CS Teacher’s Manual. In the weeks leading up to my planned writing activity, I found that working up to actual writing with a few smaller activities (one per lesson) as we approached the end of the Reading Steps helped students lay the foundation for successful writing of notation.

While spending this much time on manuscript writing might seem like overkill in some classrooms, other populations need the time to process this activity. One of the tricks to teaching groups that struggle is to find engaging ways to work in lots of practice and review time into the lessons that don’t bore the class and teacher alike.

Some of my favorites techniques for CS rhythm units from the Teacher’s Manual are: “Human Rhythm,” “Rhythm-Cards,” “Popsicle Sticks,” whiteboards and then finally a worksheet. The “Human Rhythms”game is a great starting point opening up the discussion of notating left to right. Rhythm-Cards take the pressure off penmanship and allow the students to notate as fast as they think without worrying about neatness. “Popsicle Sticks” work well, giving the class the opportunity to slow down and space out the notes, practicing the thinking process needed in dictation.

My Writing Procedure:

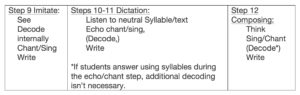

I casually run the class though CS Steps 9-12 on each of these activities, one Technique (maybe 4-6 minutes long) from the Manual in each lesson. I use this as a time to walk the class through the thinking steps of writing, setting up the dictation and creation process. When you think about it, each Writing Step is just a combination of previous Conversational Solfege steps plus penmanship. Dr. Feierabend has jokingly called this Feier-Math: Steps 3 + 9 = Step 10, Steps 4 + 9 =11, and Steps 5+9=12.

Regardless of which technique I use, my objective remains the same, to lay the foundation for notating musical thoughts. Below are the steps I take at each level, connecting the earlier Conversational Solfege Steps to the Writing Steps, while always encouraging musical thinking first.

Step 9

At the start of the writing activity I say to the class “make this pattern.” I hold up a flashcard with a pattern and invite students to copy that pattern while I watch and note the rate the class is able to render a simple copy. I run a couple more Step 9 examples to improve the speed of answers as they become familiar with the activity. To ensure that the musical thought process is engaged right from the start, I begin Step 9 asking the students to see the pattern, decode internally (using inner hearing,) sing/chant, and finally, write. During the write step is where the fun begins. As I mentioned before, there are many Techniques from the CS Manual to be used at this step. For example, in the Technique “Human Rhythms” the children scramble into position to form notation and the class reads must decode their rhythmic pattern.

Steps 10 & 11

Between each example, and when I’m ready to move onto Steps 10 – 11, I say “Clear your board (or whatever the making space is) and listen to my pattern and echo.” This is so the students are not looking at the last pattern while imagining the next. If it sounds accurate then I invite them to “decode it,” by singing or chanting, and if they are accurate I invite them to “write it.” If I was doing “People Notes,” it’s at the “write-it” command that I let them go to their places. First I do a couple familiar patterns then a four beat excerpt from a familiar song, inviting the students to listen and echo. For example, I’ll sing “right, right, right, left, left, left, both, both, both, down, down, down.” If the echo is good, I ask them to decode the excerpt, and then write it out. I’ll continue these steps for a couple unfamiliar (Step 11) patterns and songs as well

Step 12

Once the class has done a couple familiar and unfamiliar patterns and songs, I invite them listen and respond and I do a couple rounds of Step 5 (Conversational Solfege- Create.) In other words, they need to think for themselves. Holding up four fingers representing the four beat spaces I want students to fill, I say “Give me your attention and respond…think for yourself” and I sing a pattern to start out with and allow space for the class to respond. We do this 2-3 times and when it starts to sound like musical thought I ask them to “repeat your answer,” and “one more time…now write it.” Most often the children sing their answers with syllables, if they don’t then it’s necessary to insert a decoding step before writing. For accelerated learners who need more of a challenge, when giving their answers during the sing step, I ask them to give arioso style answers using words and rhythm/melody, four- or eight-beat phases. The result is students decoding their own invention and practice writing both notes and lyrics.

Tonal units use the same process, but with slightly different activities. My favorite Techniques are “Hand Staff” (pp. 51, 53, 56,) introduced from the start of Step 6 when Reading begins. This basically means that students are using their own hand as a staff, which is portable and always available for quick dictation while waiting in line, as a time to silently respond, lowering the classroom sound level. The added benefit is that it mimics the actual musical staff nicely. I have everyone in the room always answer with hand staff if it’s not their turn. My next favorites are “Floor Staff” (pp. 51, 53, 57,) and then “Tone Cards” (p. 51,) “Placemats and Poker Chips” (pp. 51,53,56,) and worksheets. Leading up to actual paper and pencil writing of notation with these playful activities brings the entire class into the fold of music literacy while allowing for individual learning needs.

Alternative writing activities also make great review activities, recalling concepts from past units while focusing on a new element in the current unit. For learners who need support developing a love of literacy, preparing the Conversational Solfege Writing Steps through activities before putting pencil to paper pays off by allowing processing time for those students who need differentiated and social learning opportunities, low pressure assessments and a chance to feel like academic equals with the more accelerated learners in the room.