The Play-Party: A Tuneful, Beatful, Artful Way to Play:

Including play-parties as the ‘doing’ part of a lesson.

By Emily Maurek — Lake Central School Corporation

FAME Endorsed Teacher Trainer

It is well-known to First Steps in Music and Conversational Solfege practitioners that the use of authentic folk music in their classrooms is a vital, enriching and delightful part of the music class experience. Quality folk literature also provides students with rich repertoire that offers appropriate text, key, vocal range and tempo and what John Feierabend calls the “art part” of music (Feierabend p. 89). To this vibrant brew add the fun and playful context of a ‘game’ such as a play-party and it’s the type of activity that makes students excited to come to music class. When teaching with a Feierabend focus, spending significant time joyfully “doing” music is essential in connecting with one another and finding what Feierabend calls the “4th dimension” or the expressive, below the surface message of music (Feierabend p. xxi).

It is well-known to First Steps in Music and Conversational Solfege practitioners that the use of authentic folk music in their classrooms is a vital, enriching and delightful part of the music class experience. Quality folk literature also provides students with rich repertoire that offers appropriate text, key, vocal range and tempo and what John Feierabend calls the “art part” of music (Feierabend p. 89). To this vibrant brew add the fun and playful context of a ‘game’ such as a play-party and it’s the type of activity that makes students excited to come to music class. When teaching with a Feierabend focus, spending significant time joyfully “doing” music is essential in connecting with one another and finding what Feierabend calls the “4th dimension” or the expressive, below the surface message of music (Feierabend p. xxi).

Play-parties are ideal as a “doing” part of a lesson. Not only are play-parties joyful, but they are also a reminder of Americas’s history and are a living, breathing example of a pastime children enjoyed over one hundred years ago. Play-parties are also filled with the expressive qualities that encourage our students, especially upper elementary, to be tuneful, beatful, and artful.

What is a Play-Party?

A play-party is both an activity and an event. By definition, the play-party is “a social gathering especially of young people characteristic of the rural U.S. with entertainment consisting of dramatic games and swinging plays performed to the singing of ballads and clapping usually without instrumental accompaniment” (merriam-webster.com). Play-party songs and dances were largely children’s singing games brought to the United States by immigrant settlers from England, Ireland, Scotland, and Germany. Also, important in the history of the play-party were the religious affiliations of those settlers, Protestant sects, who discredited the playing of instruments and viewed dancing as a “wicked sport” (Wolford p.12). However, to those same groups the act of simply playing games was considered a time-honored, unsophisticated and charming pastime that brightened life on the frontier (Rohrbough p. 3) that was, therefore, acceptable.

Play-party songs and games thrived in more geographically isolated areas, especially the Midwest and frontier regions, during the late nineteenth through the early twentieth centuries. For this reason play-parties were largely considered to be a country amusement (Wolford p. 12). Less than one hundred years ago there were places where the play-party still remained — due to geographical inaccessibility (hills, mud roads), lack of outside influence, and towns that were far apart (Wolford, p. 11). Play-party games and songs were exclusive to America (Botkin p. v) and can also be considered one of America’s most important contributions to the world of folk dances and folk games (Riddell p. 3).

Play-party songs were well-known and were often passed down in the oral tradition from generation to generation. The songs themselves tended to be four-line verses, sung three times followed by a refrain. There was a repetitive quality, in both phrasing and text, and they were easy to remember. But, as folk tradition dictates, words might be misheard, forgotten or changed over time. Nancy Glen says play-parties “…were sung in their original form, or with added verses reflecting names of local people, occupations, and geographic features of the area. Verses might be added spontaneously during a play party, and might travel with the song as it was carried to other locations”. Melodic lines were also borrowed from other songs, and other lyrics sung to the same melody to create play-parties with similar tunes, different words, and varying games. A great example of this is the song “For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow” which can be found in the play-parties Pig in the Parlor, All Go Down to Rowser’s, and We Won’t Go Home Till Morning. This re-composition by players was a reflection of locality and the social commentary of the time with songs and games changing and adapting to area culture. In some areas the songs changed structurally “… to include call-and-response segments, improvisation, syncopation etc. as a reflection of an African influence as traveled from the rural South to the urban North”. (Nettle p. 97)

There is definite English influence in play party melodies in both tonality and characteristic. One noticeable clue is the lack of harmonizations in play-party songs because, as Sharp describes, they are sung by those whose harmonic sense is underdeveloped (p. 57). Folk melodies also inherently non-harmonic and do not modulate (Sharp, p. 88). In terms of tonality, the majority of play-party songs are ‘do’ hexachord melodies (do, re, me, fa, sol, la) which is firmly characteristic of America’s folk tradition. Some modes are present, like mixolydian (Going to Boston), dorian (Old Betty Larkin) and, very rarely, the aeolian mode (Weevily Wheat). The latter example, Wolford says, is a sign of the song’s age (p. 107). Weevily Wheat is a fascinating example of a song traveling and changing through history. Botkin (p. 345-6) suggests the song has eighteenth century English origin. Variants of the tune and text can also be found under different titles such as “Charlie’s Neat”, “Charley”, and “Over the River to Charlie”.

The vast majority of play-party songs are ionian but some play-party melodies become unconsciously transposed into other modes. Sharp describes this as a regional phenomenon “where certain singers transpose almost every song into one particular mode” (p. 126). The minor scale is absent from play-party songs and is primarily found in composed melodies. These give rise to the suggestion the majority of English folk tunes which were brought to America were introduced at the time of the early settlements served as models for the development of the more “recent” tunes (Wolford p. 124). Play-party songs are either based on traditional pieces from the old country or newer indigenous pieces like American songs (Botkin p. 54). These newer pieces were popular melodies of the day, which often retained the melody but changed the lyrics of a song to reflect the movement of the games they were playing. Some examples of this are The Little Brown Jug, Shoo, Fly Don’t Bother Me, Turkey in the Straw, and Jim Along Josey (Brown p. 4).

Types of Play-Parties

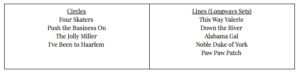

Based on formation and game type, play-parties can be divided into different categories. The most common were the circle and ring formations which were most closely tied to England and the maypole dance (Seeger). Circles were the preferred formation for play parties and some games included two circles, moving in the same or opposite directions, facilitating use of the promenade hold and swings by partners in the game. In a circle game, there is no “head couple” to dominate and circles also accommodate the shyer and novice players. Some play-parties could be considered “song dances” with full directions built into the text like Old Brass Wagon, Star Promenade, and Circle Right.

There were also play-party games in longways sets, most notably echoing the formal dancing of the day with figures taken from square and reel dances but in a manner that was considered acceptable to the community. Proof of this is found in the multitude of longways play-parties that echo the movements of Sir Roger de Coverley and Virginia Reel, like Weevily Wheat. There are also stealing and choosing figures in both circle and line formations where a player with no partner, at some point, steals (or chooses) a partner in the course of the game. Down in the Valley, Pig in the Parlor, Skip to My Lou, Jolly Miller, I’ve Been to Haarlem, and Old Dan Tucker have this action.

Lesser known by today’s standards are other types of play-party games like kissing and marriage games, games with the imitation of work, and games with dramatic acting and no prescribed movements. Lesser known were choosing games containing the paying and redeeming of forfeits, or dares (Wolford p. 110). Redeeming a forfeit meant performing a stunt like wading in the pond, kissing a rabbit or whatever dare players could dream up.

The Play-Party: An Activity

At school, play-party games and songs were common amusements as well, but teachers had to bridge whether or not to allow play-party games to happen at school. Rural area school boards in Indiana fell to pressure from parents and religious leaders that they could not “afford to hire teachers who allow dancing and play-party games on school grounds” (Wolford p. 18). So it usually went that students between the sixth and twelfth grade would steal away at recess and at noon to play where a teacher was not likely to find them. Interestingly enough, in larger urban areas play-party games and folk dances were taught to students at school, presumably during the school day or openly at recess as children entertained themselves (Wolford p.18).

The Play-Party as an Event

The play party event had different names depending on the region. Glen describes common terms used to describe play-party events, also known simply as ‘The Plays’ — games, frolics, swing games, and ring games. Glen describes full of imagery more descriptive monikers for a play-party like the terms “bounce-around” which described the boisterous nature of the games and “gin-around” a term that derives from the circular nature of the games and was similar to the movement of a horse or oxen-drawn grinding gin.

In some communities the play-party was the most popular social gathering. Each family would take turns hosting and, during warmer months, play-parties would take place as often as twice a week. Play-parties also coincided with harvest and planting times, weekends, and the various “bees” so common in country life. Invitations would go out via word of mouth, by a rider who went by horseback from house to house, or in later years, by telephone party line. Play-parties were held in the evenings, indoors or out, and were usually timed with full moons. Simple, inexpensive refreshments were served like watermelon, cake, ice cream, nuts, and candies (Wolford p. 15-16). Attendees arrived at dusk and often stayed until no later than the early dawn because the men in particular had to get home for the daily chores.

Practically everyone participated in the games because most remembered the songs and steps from their own childhoods. Onlookers (usually the married and unavailable) would sing and support the games on the sidelines while at the same time keeping a watchful eye. The young adults of a certain age might slip away and hold their own game in another room, usually kissing games (Botkin p. 25).

No callers were necessary for play-parties because the words of the song told participants what to do. With the tune and text being interchangeable participants quickly learned the steps as they learned the tune. Even though there was no instrumental accompaniment, play-parties had all the hallmarks of social dancing but singing was the accompaniment so the dancing permitted. If instruments were used and a caller was needed to tell the dancers which steps to execute, it was called a dance (McDowell, p. 55). But fortunately a play-party had no need for instrumental accompaniment because “If you are playing the game yourself…you won’t have time to play an instrument anyway.” (Jones, p. xx)

Decline of the Play-Party:

In 1917 Wolford laments that “…conditions in Indiana have recently grown unfavorable, and it is only in a few remote districts that the play-party has not been lost or forgotten” (p. 11). These country amusements started to decline in the early part of the 1900’s for many reasons, mainly social and economic. The same play-party hosts or attendees were increasingly drawn to town by the establishment of motion pictures. Boys in particular, were also lured to town by pool tables. Improved roads, rubber tires, and increased railway travel increased mobility from country to town. By 1930s and 1940s and with radios common in American households (Spurgeon p. 57) and the country was transforming into a society of music consumers rather than music makers.

Play-Party Teaching Techniques

There are many benefits to teaching play-parties and Pete Seeger calls play-parties: “some of the best mixers in the world!” Seeger goes on to explain that novices can join the fun without belaboring instruction and any number can join in without rigid sets. Play-parties can be spontaneous and can be done anytime, anywhere, and they are fun to sing — full of folk poetry, symbolism, and imagery.

As Feierabend suggests in the Book of Song Dances, “…most students should be ready to explore these dances starting in second grade” (p. 5). In the classroom, teach play-parties in their original context and share pieces of their history. Some play-parties can be assimilated within a single lesson while others require scaffolding to ensure student success. For play-parties with new or unfamiliar figures, start small by teaching the dance figures in one lesson and review in the next. When students can move comfortably through the figures the teacher should then sing the accompanying song. All play-parties should be presented without accompaniment, as originally intended, and the students will eventually assimilate the song for their own. If students seem winded from the moving and singing it is appropriate to divide the class into movers and singers (Feierabend p. 5) as was the tradition at play-parties with onlookers singing for and with players. It is also important to remember the artful part of play-parties and to encourage musical expression while enjoying the game.

Below is a suggested play-party teaching sequence in order of difficulty:

Ways to Share Play-Parties

Share a wonderful slice of history with parents, fellow teachers, administrators, and the community by including play-parties as part of a family folk dance, informance, or international night. Include all students in learning play-parties as part of pioneer days. Performing play-parties for an audience is possible, though not the original intent, but can demonstrate history in action. In this instance, consider giving a few brief remarks about the historical context to the audience beforehand. Adding light acoustic accompaniment in this setting can highlight the melody and form of a song but energetic singing by participants demonstrates a more robust, interactive experience.

Since being (or becoming) tuneful, beatful, and artful in the upper grades is of the greatest importance, utilizing play-parties is an excellent way to continue developing and reinforcing these skills while using traditional folk music. Take a moment to remind students that there was a time in history when children had to entertain themselves without the aid of technology. Today, the greatest compliment to the music teacher would be to catch students playing these games at recess on their own. Celebrate this uniquely American art form with your students and keep history alive joyfully!

Resources:

Botkin, B. A. (1937) The American Play-Party Song: With a Collection of Oklahoma Texts and Tunes. Lincoln: University of Nebraska

Brown, Maya (2017) “Jim Along Josey:” Play-Parties and the Survival of a Blackface Minstrel Song” Excellence in Performing Arts Research: Vol 4, Article 3

Chase, R. (1967) Singing Games and Play-Party Games. New York: Dover Publications

Feierabend, J.M. & Strong, M.S. (2018) Feierabend Fundamentals. Chicago: GIA Publications

Feierabend, J.M. (2014) The Book of Song Dances. Chicago: GIA Publications

Jones, B & Hawes, B.L. (1972) Step it Down. New York: Harper and Row

Nettl, Bruno (1976) Folk Music in the United States an Introduction. Wayne State University Press

Newell, W. W. (1903) Games and Song of American Children. New York London : Harper & Brothers

Play-Party. (n.d.) In Merriam-Webster’s collegiate dictionary.

Retrieved from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/play-party

Rohrbough L. (1940) Handy Play-Party Book. (Revised in 1982 by & Riddell, C.) North Carolina: World Around Songs

Seeger, P., Seeger, M. & Eisenberg, L. (1959). [Liner notes]. American Play Parties [Record Album]. Folkways Records

Sharp, C.J. (1907) English Folk Song: Some Conclusions. London : Simpkin & co., ltd.

Spurgeon, A. (2005). Waltz the Hall: The American Play Party. University Press of Mississippi.

Wolford, Leah J. (1917) The Play-Party in Indiana. Location: Publisher

Journal Articles:

Glen, N.L. (2017) Why Do We Skip To My Lou Anyway? Teaching Play Party Songs in Historical Context. General Music Today, 30(2), 4-10

Howle, M.J. (1997). Play-party games in the modern classroom. Music Educators Journal, 83(5), 24

McDowell, F.L. (1955?) Folk Dances of Tennessee. Delaware, Ohio: Cooperative Recreation Service, n.d.

McEntire, N.C. (2002) The American Play-Party in Context. NY Folklore Volume 28 Spring-Summer 2002 p. 30

Piper, E. F (1915) Some Play Party Games of the Middle West. The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 28, No. 109 (Jul. — Sep., 1915), pp. 262-289 Published by: American Folklore Society Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/534423

Sackett, S.J. Play Party Games from Kansas. Retrieved from https://esirc.emporia.edu/bitstream/handle/123456789/1546/S.J.%20Sackett%20Vol%205%20Num%203.pdf?sequence=1